News Details

Academia is a challenging environment. Having a good mentor that can offer the right kind of help at the right moment can make or break one’s career, yet academics are often left to their own luck and devices when it comes to “mentorship.” How can one create a good network of mentors? What does it take to become a good mentor? What is mentorship and why is it important?

In three KLI Lab sessions, our fellows organized discussions to collectively raise awareness about the importance of mentorship and to develop conceptual frameworks that can guide our beliefs and actions on this matter. Initiated by Stephanie Schnorr and Nicole Grunstra, we organically developed a collective play of three parts that, in hindsight, perfectly merged our imaginative, cognitive, and practical faculties. With this report, we’d like to invite you to come play with our thoughts and ideas, too.

Imagination: let’s start with a thought experiment

FL Holmes’ “Investigative pathways” found that mentorship was the most consistent factor among famously successful experimental scientists. There was a clear need to address the central role of mentorship in our professional lives, but what does it mean and how should we go about creating it?

Guido offered a way to think about the role of mentorship”: “the professional academic life is all about cultivating relationships.” We can rethink our academic lives from this perspective by way of a thought experiment. You can join us in this exercise by imagining the following elements and putting them together in a coherent and integrated picture in your minds.

- A room, of any dimension and shape and form and structure, in which you would like to occupy and work.

- Lighting for the room, of any format, source, abundance, luminosity, temporality, etc.

- A library of any media containing information that is important, relevant, or interest to us, or deriving from our own productivity.

- Consideration that you will receive visitors, and so creation of a space/furniture/setting within the room to receive these visitors.

Give yourself sufficient time to cultivate this image. In our lab session, we asked each person to pick out and share particular elements of their rooms— whatever they found notable or interesting—or to just generally describe their rooms.

This thought experiment was designed by Stephanie to be implicit about how the room maps onto real-world relationships or mentors. The goal is to let everyone draw their own associations or focus on what had meaning for them, and if they wanted, to share this perspective. The thought experiment places a form of structure in our academic, professional lives by integrating and connecting it with our personal lives as well. In the end, it was very enriching and extremely diverse to hear how people architected their workspace in their minds.

These mental rooms contain our productivity as well as our connectivity to others, past and present, who have been or are mentors and mentees to us. How would we see ourselves situated in this professional space with regards to mentorship? How has it influenced us? What do we see from our own experience or work life that we find of value to share with others?

Theory: let’s develop an evolutionary perspective of mentorship

After the previous session, our fellows decided to run two more sessions to propose a theoretical framework for understanding mentorship and then its application in our lives. What is mentorship? How does it work? Can we codify and institutionalize it in ways that can benefit our academic lives?

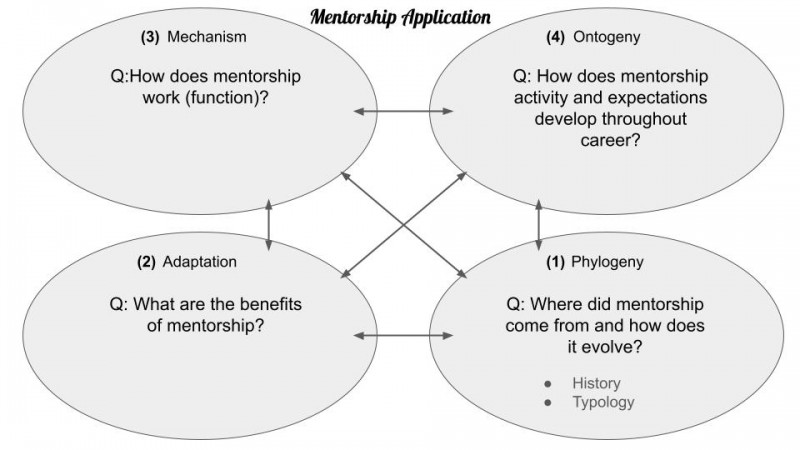

We, as humans, are ultimately social creatures that rely on our relationships for survival and well-being. Social learning is at the foundation of the success of our species. Therefore, Guido and Nicole suggested that we start with Tinbergen’s Four Questions on animal behavior: mechanism, ontogeny (development), phylogeny (evolution) and adaptive significance (function).

Applied to mentorship, the four questions would be:

- Mechanism: How does mentorship work (function)?

- Ontogeny: How does mentorship activity and expectations develop throughout our careers?

- Phylogeny: Where did mentorship come from and how does it evolve?

- Adaptation: What are the benefits of mentorship?

It is clear to us that this framework applies to mentorship as a human behavior and relationship. Mentorship is a kind of relationship that is built, grows, develops, and has hierarchical value (mentor or instructor to student or apprentice). It has a clear function—an adaptive value. It also works in a particular way, for instance, through one-on-one instruction or as a cultural phenomenon in groups. From a phylogentic perspective, mentorship can form lineages and the act and practice of mentorship can also be inheritable. Depending on the culture of the lab or academic group you mature in, you might form mentoring behaviors and beliefs that are carried out elsewhere. In any case, we already understand and make salient mentorship relationships in terms of “academic pedigrees.”

When we take a step back to think about the conditions that create, enable, or disrupt mentorship, we can also think in terms of Tinbergen’s Four Questions:

- Mechanism: How does the system of mentorship influence the mechanisms that enable mentorship programming?

- Ontogeny: How does experience influence the development of mentorship?

- Phylogeny: How does history or procedure predetermine acceptance, expectations, and implementation of mentorship?

- Adaptation: When experiences influence mentoring behavior, how does this new variation modify success?

Each fellow offered their own answers to these questions. We invite you to do the same.

Practice: let’s build our own mentorship network

The KLI is a unique place with its own conditions for unique types of mentorship: the constitution of the institute is transient and dynamic, which can offer opportunities for fellows to get away from entrenched institutional cultures and politics and the freedom to form new relationships with those outside of their regular, disciplinary networks.

In this last exercise, we reflected on the types of mentorships that can happen at the KLI. We sought out models of mentorship in other institutes, countries, or beyond academic in the industry. Many universities in the US have also institutionalized mentorship programs into the benefit packages of tenure-track academics to help them succeed. Fellows with industry experience remarked that mentorship programs are often built into their workplace as it is an investment in the company’s workforce.

Mentorship is not a given

Mentorship is not a given, either to the mentor or to the mentee. Not everyone knows how to do it properly, to know what mentees might need to succeed. Yet mentorship is often the solution and key to forging a way out in academia. Our three-part activity was a way for fellows—mostly early career scholars in their postdoc and late-stage PhD phase— to have the opportunity to reflect on the kind of help they need and the kind of help they can eventually offer.

This text, written by Lynn Chiu, was developed by interviewing Stephanie and Nicole.